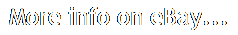

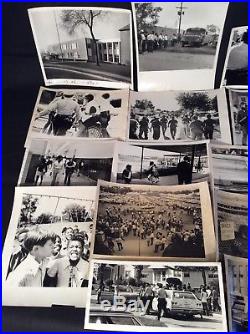

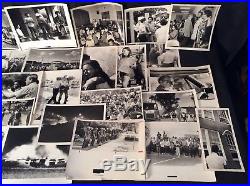

RARE 1971 PONTIAC MICHIGAN BUS RIOTS Press Photo Lot 87 RACIST African-American

RARE 1971 PONTIAC MICHIGAN BUS RIOTS Press Photo Lot 87 RACIST African-American - these photos are all original TYPE 1 Photos from the Oakland Press Archives. This was the most volatile time in Pontiac Michigan history, post the Detroit'67 Riots...

This was an integration issue, with schools being either predominately 90% black or white. These are truly a piece of Michigan History.

To think how far we have come in the last 48 years! Below is a very detailed explanation of what was occurring in Pontiac in 1971. This was a major civil rights injustice!On a hot steamy August evening in Pontiac in 1971, a few days before the start of a new school year, 10 school buses exploded in a ball of flames that lit up the night sky as well as the ugly side of a national controversy. At about 10 oclock that night, at least two persons slipped through a hole cut into a six-foot wire fence surrounding an unguarded northside bus depot. They placed dynamite atop the fuel tanks of six of 13 buses parked along the fence, lit the fuses and ran.

The resulting blast destroyed 10 school buses, damaged three more and focused national attention on Pontiac, an industrial town of 84,000 outside of Detroit. The divisive busing issue had simmered in the city for nearly 20 months, but there had been no violence until the bombing.

Jackson said he hoped that the bombing would wake up the people of Pontiac to the fact that they have unsolicited helpradicalsthat they dont want. Pontiac is the new South, an unnamed state legislator said.

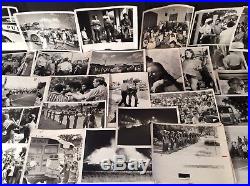

In the eerie light of burning buses, emotions which had simmered beneath the surface of the city came to a sudden boil. Residents standing across from the burning inferno shook their heads in disbelief. To be sure, there was more to the controversy than mere bigotry many were truly concerned with maintaining traditional neighborhood schools but few would argue that Pontiacs racial situation was not a major reason for the strife. Almost everyone who lived or worked in Pontiac was a blue-collar production worker. General Motors Fisher Body and Pontiac auto-assembly plants employed 35,000 residents.

Pontiacs black population had risen to nearly 30 percent in the late 1960s and black enrollment in the citys schools doubled between 1957 and 1967. Most of the black population was concentrated in the citys south side, where many neighborhoods resembled the worst of big city ghettos. Although a few blacks had integrated some neighborhoods in the near east and western parts of the city, the rest of Pontiac was virtually all white. As in most industrial towns, many of the whites had migrated from the South in search of better jobs, bringing with them their southern values and prejudices.Pontiacs racial problems intensified after the Detroit riot in July 1967. Despite an open occupancy law passed in the city, the schools and the neighborhoods remained racially polarized. Early in 1969, Elbert L. Hatchett, then president of the Oakland County NAACP, filed suit in Federal Court complaining that Pontiac schools were deliberately segregated. Schools were either 90 percent white or 90 percent black.

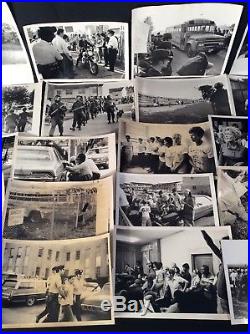

Keith, the only black jurist on Detroits district bench, received the case assignment. While the case languished in the courts, race relations in the city worsened. Confrontations ranged from a lock-in of the school board by militants, to sit-ins by blacks at the citys two high schools.

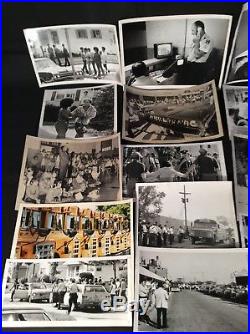

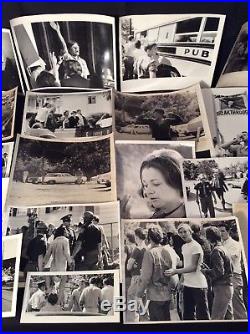

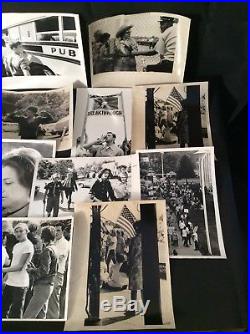

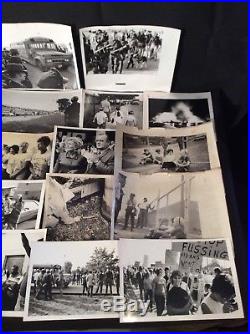

The school board finally agreed to a compromise by putting the new school near downtown. In February 1970, Judge Keith, having ruled that Pontiacs school board intentionally perpetuated segregation, ordered the district to bus pupils to achieve integration by the following fall. Keith, in response to school board claims that it had adopted six resolutions since 1948 aimed at achieving racial balance, then declared: Pronouncement of good intentions with nothing more amounts to monumental hypocrisy. School officials filed an appeal and succeeded in delaying the busing order. Fighting between students at the two high schools broke out sporadically, and Mayor Jackson imposed a curfew for minors. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Keiths decision. The Pontiac board then voted to appeal the issue to the U. Supreme Court, but agreed to implement a busing plan. Opponents continued efforts to block busing by petitioning Congress to pass a law that would ban the practice. The movement was spearheaded by a local homeowners group called the National Action Group (NAG), which claimed more than 20,000 supporters with 71 chapters in Michigan and 10 chapters in other states. NAG, led by a fiery 36-year-old housewife, Irene McCabe, continued to fight court ordered integration. McCabe rode the tide of resistance to national attention by proclaiming, There are millions of little people in this country who want to preserve the neighborhood school and all it means to the American way of life. McCabe insisted that she and her followers were not against integration, only against busing to achieve it. I went to school with colored kids myself, she said. NAG claimed to have no affliation with the Ku Klux Klan or other hate groups.Her popular NAG sweatshirts proclaimed her distrust for the courts: Bus Judges, Not Our Children! Members kept their children home from school, staged sit-downs along bus routes, enrolled their children in private and parochial schools. After the rear-end assembly of a bus fell off in the first week of busing, NAG added unsafe buses to its list of reasons why parents should demand an end to school busing. I cant in good conscience tell parents, black or white, to send their children to school where friction is so great that theyre going to the hospital day after day, insisted NAG attorney, L. And theyre riding buses unfit to be on the highway.

William Waterman, an attorney for the NAACP, said Pontiacs black community had watched NAG grow into a huge and terrifying dragon of racism. I can honestly understand the white resentment to busing, he said. But dont they see that its really not busing were talking about? The real issue is equal and I cant stress that word enough equal education.For-sale signs mushroomed in the white neighborhoods. A record 600 homes went up for sale, one third more than at the same time a year earlier. Most of the white exodus took place at the start of busing in 1971 when the district lost 11 percent of its students.

Since then the net loss has stablized to about 1 percent a year. The school term opened on time, despite damaged buses and the initial boycott by parents who resisted busing their children. School officials and PTA quietly worked to keep peace between warring groups.

Said housewife Lucille McNaughton, who headed a biracial committee to make integration work: The vast majority in Pontiac are in the middle. They want to do whats right, but theyre not sure what that is.

We feel if we stress the positive we can counteract some of the bad publicity and really give our children a better education. The Supreme Court refused to hear the busing case appwal, leaving Judge Keiths busing order unchanged. In March of 1972, the feisty McCabe and five other NAG members began a 44-day march from Pontiac to Washington to pressure congressional leaders to support an anti-busing constitional amendment. Our cause is to retain freedom, just like George Washington, said McCabe. Residents along the route joined the march and on April 27 a weary, footsore Irene McCabe plodded into Washington D.

Despite a noticeable limp, McCabe danced her first steps into Washington. But the afternoon rally her supporters predicted would attract 30,000 drew only 1,000. At the steps of the U. William Broomfield, and House minority leader Rep. Gerald Ford greeted the NAG marchers.

The following day she met with President Richard Nixons advisor, John Ehrlichman, to discuss a constitutional amendment to ban forced busing. Wallace would later ride the antibusing tide that began in Pontiac to a solid victory that fall in Michigans Democratic Presidential primary. But the school buses continued to roll. The plan to ban forced busing failed. The national politicians disappeared from Pontiac, and the spotlight shifted elsewhere.

The courts ordered 70 other school districts around the country to bus students to achieve integration with varied results. The Pontiac bombers, later identified as Ku Klux Klansmen, were convicted and sent to federal prison. The National Action Group disbanded and a divorced and disillusioned Irene McCabe went on to become a successful realtor in her home town. There is no loud battle any more.

Many black parents gave up on busing and instead began to fight for improving their neighborhood schools. Some claim the white exodus may have been beneficial, since it helped bring stability to the community. The disappearance of the most bitter and most vocal opponents of busing, it is believed, has moderated the atmosphere for those who remained. As educator William Neff said five years after the controvery: I think busing brought two divergent groups of people together and enabled them to get to know one another, to live together, to respect each other, to learn to each others strengths and weaknesses.

But did it bring about quality education? I wont say it did.Please thoroughly review all photographs. PLEASE READ TERMS OF SALE. Questions : Are typically answered within 24 hours.

We strive to take good photographs and give an excellent description of the item. The item "RARE 1971 PONTIAC MICHIGAN BUS RIOTS Press Photo Lot 87 RACIST African-American" is in sale since Thursday, February 15, 2018. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Cultures & Ethnicities\Black Americana\Photos". The seller is "ncrkook17" and is located in Stockbridge, Michigan. This item can be shipped to United States.